|

|

Posted By Cheryle Snead-Greene, Prairie View A&M University,

Tuesday, November 18, 2025

Updated: Thursday, November 13, 2025

|

The interim administrator’s guide Stepping into the role of interim administrator within a large administrative unit can be both exciting and challenging. You’re responsible for implementing policy changes that need to be effective in the short term yet sustainable over time, all while maintaining team morale. Yes, that’s a lot to balance, but it reflects the realities of the role. This blog is inspired by my recent experiences and those of colleagues in similar positions. Our stories highlight the need for practical strategies that resonate across different administrative contexts. Creating a solid structure is vital in any administrative unit. But how do you introduce necessary policies without making everyone feel like they’re stuck in a corporate meeting? Here are some strategies that we employed:

Prepare a smooth transition. Instead of launching into significant reforms, try a subtler approach. Begin staff meetings with a quick “highs and lows” round. This simple activity sets a positive tone and engages everyone from the start. Real-life Example: In a library setting, consider implementing small changes like clearer guidelines for interdepartmental collaboration. You might also introduce a “Book of the Month” discussion, allowing staff to share insights on professional development books. Such activities can spark conversation and foster a sense of community. Create a policy framework. When it comes to policy changes, clarity and choice are crucial. Instead of imposing a one-size-fits-all solution, offer a variety of options for your staff to consider. Real-life Example: In HR, you could present options such as revised work policies, new professional development programs, or updated performance evaluation criteria that include peer feedback. Empowering employees to choose what resonates with them encourages ownership and engagement. Test with a preliminary launch. As you prepare to roll out new policies, start with a soft launch. Pilot programs allow for experimentation without the pressure of full implementation. Real-life Example: In IT, if you’re introducing a new project management tool, test it with one team first. Gather their feedback to make practical adjustments before a broader rollout. Engage an advisory council. Form an advisory council of enthusiastic staff willing to embrace change. This group could brainstorm ideas, pilot new policies, and facilitate communication throughout the unit. Real-life Example: In student services, create a committee that includes representatives from various roles, such as advisors and counselors. This group could meet monthly to review student feedback collected through surveys and use those insights to develop initiatives that address students' needs. Listen to your staff. Listening is a crucial skill in this role. Schedule regular open forums or “listening sessions” where staff can share their insights and feedback on potential policy changes. Real-life Example: In a library, implement a "Feedback Wall" where staff can anonymously post their thoughts and suggestions. Set aside time each month to review these notes together as a team, encouraging open dialogue that can lead to innovative solutions. In conclusion, navigating policy changes in large administrative units requires a careful balance, especially for an interim leader. You want to provide structure while respecting the existing dynamics within the organization. By embracing small incremental approaches, offering diverse policy options, and considering preliminary launches, you can foster a culture of collaboration and innovation. I encourage you to reflect on your own experiences and share your thoughts. How have you engaged your staff in policy changes? What challenges have you faced, and what strategies have worked for you? Your insights can inspire others facing similar challenges, so don’t hesitate to share.

Acknowledgement: This blog was enhanced with the assistance of AI tools to refine ideas and improve clarity.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this post are solely those of the blogger.

Tags:

administrator

Cheryle D. Snead-Greene

examples

leader

policy change

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Alison Whiting, Mount Royal University,

Tuesday, October 21, 2025

Updated: Friday, October 17, 2025

|

Implementing an Expedited Policy Approval Process

The Policy Ask

In June of 2025, the Alberta Government introduced a new Fairness and Safety in Sport Act ( (hereafter referred to as the "Act”) and accompanying regulation.

Google Gemini (an AI tool) summarizes the legislation in the following paragraph:

"Fairness and Safety in Sport policies are regulations, particularly in Alberta, Canada, designed to ensure integrity, equity, and safety in sports, especially for female athletes. These policies, such as Alberta's Fairness and Safety in Sport Act and its accompanying Regulation, require sports organizations to implement rules and procedures for athlete eligibility and participation. The Alberta Act specifically mandates policies that limit eligibility for female-only divisions to biologically female athletes, aiming to protect the integrity of women's sports while also seeking to provide avenues for transgender athletes' meaningful participation."

The government made it clear that Post-Secondary Institutions fall under the Act and regulation, and that we had to have a Board-approved policy in place by September 1, 2025.

Now, I’m sure most of you can immediately spot the challenge of

being told in June that you need a Board-approved policy in place by September 1. Our Board of Governors meetings follow the academic calendar and we do not have any regularly scheduled meetings between June and September. Our standard policy approval

process includes a 30-day community consultation period and we try our best to ensure that consultation happens during the academic year when faculty and students are on campus.

The Challenges

So, what did we do? We first turned to our trusty Policy on University Policies and Procedures, which did already include a process for expedited policy approvals. Our Policy on Policies currently states:

EXPEDITED POLICIES

1.1 In extraordinary circumstances calling for urgent action, such as a change in federal or provincial law, a significant and immediate financial opportunity, or a major institutional risk, the President may revise

or put into effect a Policy without prior presentation to or consultation with the University’s Board of Governors which would otherwise be required.

1.2 If a Policy is revised or put into effect by the President in extraordinary circumstances, the University Secretariat will notify Employees in a timely manner.

1.3 Any

Academic or Management Policy put into, or taken out of, effect in such a manner must immediately enter a normal development process in accordance with the Policy Framework.

However, this still left us with some issues. This expedited process provides approval authority to the President, but the Act and legislation required a Board-approved policy. We were also concerned about our ability to truly follow a normal development

process after the fact when the Act and legislation had clear requirements about the policy content.

The Solution

Knowing we didn’t have a lot of time, the Associated General Counsel and I quickly took action, working closely with the executive who oversees our athletics department, to draft a policy and procedure that complied with the Act while minimizing administrative

burden and protecting athlete privacy and confidentiality.

We also engaged in conversations with our President and University Secretary to consider ways to bring this policy forward for approval given the challenges outlined above. In

the end, we decided a special meeting of the Board’s Governance and Nominating Committee in August would be the best approach, followed by community engagement activities in September.

The Board’s Governance and Nominating Committee Terms

of Reference permit them to “act on behalf of, and with the full authority of the Board on matters that arise between regularly scheduled Board meetings.” We held a special meeting of the Governance and Nominating Committee at the end of August, at

which time they approved the Fairness and Safety in Sport Policy and Procedure on behalf of our university’s Board of Governors. This allowed us to meet the Act and legislation requirement to have a Board-approved policy in place by September 1st.

Now, we were left with the challenge of how to address community engagement without the ability to conduct a formal consultation process. Again, through conversations with our University Secretary and the executive who oversees our athletics

department we decided we would bring the new Fairness and Safety in Sport Policy and Procedure to various formal governing bodies of our institution for information and discussion [which includes Deans Council and General Faculties Council (our version

of an academic Senate)], invite our campus community to share feedback with us about the anticipated impacts of the policy, and then share all the feedback collected with our Board of Governors.

Next Steps This was the first time we had to use our Expedited Policy process in this way. As a result, we are now reassessing the language we have in our Policy on University Policies and Procedures to allow for greater flexibility should we find

ourselves in this situation again in the future. We will propose changes to the language to allow the Board or President to approve new policies without following the Policy Framework and create a mechanism for receiving community feedback on policies

approved through this expedited process. With these proposed changes, we can be allowing us to be nimble and flexible in the future and still ensure transparency with our university community.

Tags:

comment period

exceptions

policy approval

policy process

regulations

transparency

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Monique Everroad, Clemson University,

Tuesday, September 16, 2025

Updated: Tuesday, September 16, 2025

|

An in-depth interview with the maestro behind the 2026 Annual Conference, Kelly Cross

ACUPA recently opened its Call for Proposals for the 2026 Annual Conference in Denver, Colorado. As a member of the Event Planning Committee (EPC), I know just how much the committee pours into making sure this conference is worth every minute and dollar spent attending.

With the expansion of ACUPA's institutional memberships, our membership stretches beyond direct policy office administrators, so many of you may not have experienced the caliber of the conference we put on each year. I also know higher ed institutions are tightening their belts under financial uncertainty. So, for this month’s post, I sat down (in front a screen) for a chat with chair-elect of ACUPA’s Board of Directors and Event Planning Committee chair, Kelly Cross, to dive into what makes ACUPA's annual conference one of the best professional investments you can make in 2026.

I hope you’ll be inspired to join us in Denver, April 20-22, and consider submitting a conference session proposal. The deadline to submit a proposal is October 16, 2025.

Editorial Note: I am convinced that this interview should have been podcast. I regret that you can’t see our facial expressions and gestures, or hear our asides. Editorial liberties were taken to ensure this post captured the essence of our conversation and came out (somewhat) shorter than a federal regulation.

The InterviewMONIQUE: What makes this year’s conference unique compared to previous years?

KELLY: We've seen a few different things over the last few years. One, we've seen increased attendance, which we love. I hope it's a reflection of how important policy administrators are on their respective college campuses. I also suspect it might be a reflection of how much we need each other and want to have a network of colleagues.

But we've also noticed that our sessions’ contents have become more and more advanced. Typically, they represent experiences or questions that folks might have if they're more seasoned in the field or they've already gone through some of the foundational elements of a policy program.

One thing that we [ACUPA] really want to focus on this year is pulling back in that foundational element in a pretty unique way. To that end, we're going to do our first ever solo pre-conference. The pre-conference is going to be focused on those foundational elements, and so it's going to be great for an individual who is new to higher education policy. We're going to talk about your Policy on Policies. We're going to talk about the intersections of shared governance, and all of those key things. I also think it's going to be good for people who might need a refresher. MONIQUE: From your perspective as a board member, and not just EPC chair, why is this conference a “must-attend” event? KELLY: Our annual conference is a must attend event for a number of reasons, not least of which for me personally is that I find it to be very rejuvenating. I am the only, you know, enterprise-wide policy administrator at my institution. That may be true for many of our members. To be able to have our own conference is great, but it's also kind of like an intensive, right? There are sessions, but you're all in this kind of cohort experience together while we're going through it. We're all attending the same sessions together and we can network in a way that is super beneficial and I think rejuvenating and energizing for the field. And so I think--there's probably a better way to say this--the bang for the buck, or the return on the investment, is excellent. I can get so much information in one place at one time and feel great about it and want to stay employed in my field work. It's really a one stop shop for me, and honestly, it's so valuable to me that even if I wasn't EPC chair and I think even if I wasn't a member of the board, if for some reason I didn't have funding, I would still personally pay to come to this conference because I need to go for myself.

MONIQUE: I've said the same thing.

KELLY: I think it's worthwhile from a budget standpoint, but I think it's worthwhile from a professional development standpoint. It gets me connected in a way that it doesn't just solve these immediate questions that I have at the conference. It gets me connected to professionals that I contact throughout the year. So, it's facilitating these kind of one-off interactions that last year-round really.

MONIQUE: And that kind of already answered my question, but what do you look forward to most about the conference? KELLY: Oh my gosh, all of it! I look forward to so much.

I look forward to the content because I know I'm going to learn something new. I also have to say I know I'm going to see people doing really amazing things. I do have to work on being OK with what I'm doing, you know, not feeling like I'm not doing enough, you know what I mean? And I think that's the other benefit of the conference is that every policy program is in a different place and we're all doing what we can and it's all, it's all good.

I look forward to that. But it's the network for me that I love so much. I have members of a ACUPA pinned in my Teams chat because I talk to y'all so much throughout the year and its one-off conversations about policies or procedure or process or how people are handling X, Y and Z. I also love the post-conference vacations that some of us take together.

MONIQUE: Yeah {sighs and looks off into the distance longingly}

KELLY: Yeah. Yeah. You know!

MONIQUE: So, I know we talked a little bit about why you and I, who are in this field, want to go to the conference. But what would you say to those folks who are part of institutional memberships who maybe don't have the word “policy” in their title? Why should they attend this conference? KELLY: So as a policy administrator, I work with a lot of people who are responsible for policy who do not have “policy” in their title, and it's because they're the content subject matter expert, the SME.

I think once you get to a certain level of an organization, the likelihood that you are responsible for a policy, and in most cases many policies, is very high. So, we have our financial compliance officer who is one of our [ACUPA] institutional members at Georgia Tech. She's responsible for like eight policies and “policy” is not in her title anywhere. I think the benefit of attending this conference for her or for an HR project manager that oversees policies for human resources is that they're getting to connect with other people who are in similar roles.

You get insight into some of the behind the scenes work that goes on so that you can more efficiently and more effectively navigate your own processes when you return to your primary campus. Also, you are hearing about how other schools manage the work and you might be able to advocate for a change in process or procedure at your own institution. Even though you may not be directly responsible for the enterprise-wide policy process, policy owners can request and advocate for quite a lot, because most policy administrators, we want it to be a good experience. So, they're looking at it from a different lens than we might be, and I think it's just going to help their own personal experience just be even better.

MONIQUE: Awesome. I think that’s great. {ready to move on}

KELLY: Yeah, I'm going to add something to that one. Sorry. So, we have had some members who are, you know, we talk a lot about higher education and our higher education policy administrators or our institutional members. But we know we have members that are staff or employees at state agencies.

MONIQUE: OK, go for it. {chuckling}

KELLY: A few years ago, we had a member from one of the Illinois state agencies who was building an entirely new office and program. And one of the things she had to do was do a lot of policies. And there is so much overlap between a higher education institution and a state agency and kind of policy, procedure, bureaucracy. She found it incredibly beneficial because she, similar to many of us, felt alone and wasn't really sure how to do things. She was able to get connected to other employees from other states who run policies for their respective unit that is not a college, and I think she still keeps in touch with them as well. So, there's a lot of benefit even if you're not in higher education.

MONIQUE: Absolutely. I agree with you. Some of the things that we talk about are so foundational to program building in general, whether we’re talking about stakeholder development or risk assessment or some of these other topics. It’s really a “plug and play.” While we all have unique lenses on higher ed, especially coming from a public institution, we have that state entity and federal bureaucracy lens that we get to carry. Like state agencies, we very similarly understand doing a lot with a little.

KELLY: Yes, yes, and documenting. {Laughs}

MONIQUE: Making it all work and documenting the heck out of it!

MONIQUE: In what ways does the conference strengthen ACUPA’s community and network and advance the mission? What impact is ACUPA having in our community, but also the industry? KELLY: I think there is a real tangible benefit that we get from being from being in the same place at the same time, where we can immediately engage in some cross-institutional dialogue around what we're learning in the moment so we can engage in the “pair and shares.” We can formulate opinions. We can make recommendations that other schools might consider that would not have popped up, in an otherwise organic way.

And it’s also not recorded. So, people are more willing to say things that they may be less inclined to put in a forum post or e-mail to someone. You kind of get the real, off-the-cuff responses from other policy administrators that might be more.

MONIQUE: Well, I think of the depth of what you can provide to somebody in these spaces, right? We understand confidentiality and sensitivity. We get what you might be inferring, but you can finally just say out loud, “this is a really tough situation I’m dealing with,” without it sounding like you're whining about your job.

KELLY: Yeah, absolutely. We can get to--and I think you hit it--we can get to that depth of knowledge and depth of sharing that is very difficult to do via a forum post or an e-mail and because we're all together. It's much more effective. You're not having to schedule 15 30-minute meetings to try to figure things out.

MONIQUE: Yeah, I just feel like sometimes like our conferences are so intense, because you're taking in so much that like, I leave and there's that high that we're all together, and then that low that I'm worthless and not doing enough {laughs}. And then there's like this middle ground that’s like, “OK, what can I do?”

KELLY: No, that's exactly it, Monique. “What can I do immediately? Because I see all of the amazing things that my colleagues are doing. How can I do a smidge of it?” But I think we're all feeling that because we all want to do good work. We're all trying to do more with less.

MONIQUE: Well, let's jump into impact of the organization. How is this conference advancing this profession? KELLY: One, this is really, to my knowledge, the only conference where we are focused on policy administration, right? It is not a backburner topic at a larger organization. You know, every single session is going to be applicable, and every single session is going to bring some advanced knowledge, interest, skill, right? And all of those things drive the profession forward. There are so few of us at our respective college campuses, most of us are in office of one, or half of one… unless you're Tony Graham and then you have 12 people.

{both start laughing}

MONIQUE: You’re totally right. This is going in... “unless you’re Tony Graham” –

KELLY: --unless you're at the University of Pittsburgh, and you got a billion people working with you… I think that being together at the conference, it gives us some weight. In a way, it is advertising that the profession and field and organization exists. I think in general, getting people together as a field of study and field of work to share ideas, share knowledge, share expertise, moves, moves the functional area forward.

We come from a lot of different places and [policy] is one of the critical elements of the seven elements of an effective compliance program, right. And this is the only conference exclusively focused on one of those seven. You know, auditors have their conference and organizations, but this this is specific to policy. And that has far, far reaching impacts, right? If we're saying that this is a standard for the field, it has huge impacts for our larger compliance programs and how those functions work together or don't work together. MONIQUE: We’ve talked about how the conference has really become more and more advanced. How does the conference support the policy program maturity levels of all possible attendees? KELLY: There are some targeted aspects of it where we're going to hit people who might want either new foundational knowledge or a refresher on foundational knowledge.

There's going to be a benefit to employees who are kind of moving from their initial years in the field to more senior roles. Even if you have all the experience in the world with policy, so much our success and ability to do good work is dependent upon others in an in an institutional administration or where we are in the organization.

What if we suddenly have an executive leader who wants to change a lot of things that goes counter to your established process? Revisiting those foundational elements can be very useful. Or connecting with individuals from schools who are doing things the way they want to switch to.

Or maybe you're starting a new job and you need to reconnect to see how people are doing things. Things are never static. We think we've solved a problem and then the problem circles back around. People change and so questions that have been asked and answered years ago come back around, and I need to remember why the answer I provided years ago or the decisions we made years ago may not be relevant anymore or may not be enough. Times have changed, y'all. Doesn't matter how much experience I have, this is my first experience--

MONIQUE: --with this rain fire?! {throwing hands up in the air}

KELLY: Bam, that's exactly it! This is my first experience being a policy administrator after 183 executive orders.

You know, I'm at a state institution, the leadership of our Regents, our legislators, those change. So even if I stayed the same, the things around me are changing and I need to be prepared to respond and do so in an informed way. Which is why I think colleagues who have that experience are incredibly valuable, like you, Katheryn Yetter, definitely. And Tony “I have a million employees” Graham.

MONIQUE: Last thing, what is one thing you hope every attendee takes away from this conference, this year's conference? KELLY: Yeah. {sheepishly} So, I'm going to say that there are two things. I know you asked for one thing.

MONIQUE: {rolls eyes and laughs} I hate you so much. Nothing's more Kelly than that statement. Go for it.

KELLY: So first of several things is: YOU CAN DO THIS. You can do the work.

There are resources and people who want to help each other out and it can be very stressful trying to figure out what to do first and then what to do next. And you can figure it out and we can help you.

Which leads into the second thing that is YOU ARE NOT ALONE. You're not alone in this field. You may be the only person on your campus with the title. You may feel alone, but you're not alone with us. We got your back and selfishly, maybe not selfishly, but--this is my personal perspective, right-- what I gained from attending this conference are the things that kept me in the field. I alluded to this before, but I was really ready to leave the field, and then I attended one of ACUPA’s in-person conferences and I really felt like I could just breathe. I could take a deep breath again and I didn’t have to figure things out by myself. I had a team of people that I could connect with, and the work felt much more achievable.

We collect feedback via surveys at the end of each conference, but please feel free to share what you find most valuable about attending the annual conference by emailing the EPC at events@acupa.org.

Tags:

colleagues

community

Conference

Continuous Learning

Events

Interview

Monique Everroad

Policy Administration

Professional Development

ROI

value

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Cara O'Sullivan, Utah Valley University,

Tuesday, August 19, 2025

Updated: Monday, August 18, 2025

|

Forging Accessible and Legally Sound Policy Language As a regional teaching institution with an open admissions model, Utah Valley University (UVU) is committed to making education accessible to all in its service region. To support this commitment, the UVU Policy Office strives to make university policy accessible to the university community. We are uniquely positioned to do this: our two-member team consists of two trained and experienced editors, and we are housed within the Office of General Counsel (OGC). Our senior editor, Miranda Christensen (who you may recall from an ACUPA online seminar she conducted) brings experience with Plain English from a previous position at an education company. Our attorneys, with their varied backgrounds and expertise, often participate not only in the legal review of drafts, but also as integral members of drafting committees. Since the Policy Office became part of OGC two years ago, we have developed a partnership with OGC attorneys to craft policy language that balances legal accuracy with clarity for their intended audience. In this article, we’ll explain how the UVU Policy Office editors and OGC attorneys collaborate by sharing their editorial and legal expertise and by using MS Teams and AI tools. The Quest for Accessible Language Step 1 Our drafting committees are chaired by a policy steward tasked with drafting policy and leading the draft through our process. The Policy Office editor assigned to a policy provides ongoing editorial support and guides the policy steward throughout all phases. Once a drafting committee finalizes its draft, it submits it to the Policy Office for a comprehensive editorial review. Step 2 In addition to typical editing tasks, the Policy Office editor conducts readability tests. The one we rely on the most is the Flesch-Kincaid test. These readability tests help us determine whether the draft is at a reading level that is appropriate for its intended audience. For example, for policies intended for students, we try to keep the reading level at Grade 10 to 14. For policies intended for faculty and graduate students, a higher reading level is appropriate. (We have not yet established a concrete Plain English rubric with formalized recommendations for reading levels and audiences—we hope to return later with another blog post about that.) Step 3 If the editor determines that a lower reading level would be appropriate, they discuss this with the policy steward and the assigned attorney and begin their work. We have experimented with using AI (CoPilot or ChatGPT) as a tool to help us simplify complex passages. We may use prompts similar to this: Simplify this paragraph into plainer English:

{Text inserted}

“Recast this text into reading level 12.”

{Text inserted} Step 5 Once AI provides the revised paragraph, the editor reviews it to determine if it is sufficiently recast and if it fits the tone and context of the policy. Often, the editor makes further revisions. When the editor completes making the revision, they tag it with a comment. In this comment, the editor indicates they used AI to help simplify the text. They also use the comment to ask the assigned attorney to review the proposed revision. The prevailing concern for the editor is to ensure their revision didn’t lose any intended legal meaning. Collaborating with our Attorneys The assigned attorney conducts their legal review to ensure the policy content is legally sound and meets compliance requirements with Utah Board of Higher Education policy, state laws, and federal laws and regulations. The attorney is also tasked with ensuring the policy language itself communicates clearly any required legal meaning.

Because we use MS Teams to collaborate during the review process, the editor, the attorney, and the policy steward can chat or comment back and forth within the document. Once the attorney completes their review, the editor, attorney, and policy steward meet to review all revisions and resolve outstanding issues or questions.

This collaboration requires diplomacy and compromise. As the Policy Office editors, we do our best to advocate for clear, accessible language, while the attorneys focus on ensuring legal soundness to protect the institution and its community. There are situations where established legal language must prevail, and others where plain language is sufficient. The editors and attorneys, along with the policy stewards, can prioritize these needs through collaboration. The result of this collaboration is a policy that has benefited from those with editorial skills, subject matter expertise, and legal expertise.

One of our attorneys, Greg Jones, said this about his experience with the collaboration between editors, attorneys, and policy stewards: “This was an ensemble project; team members respected each other’s proposed edits, even the ones that were ultimately rejected. We learned how to work with each other through the process of back-and-forth. Toward the end, a moment came when I thought everything was coming together, but I could see we had some legal problems with the draft. I saw a way to both fix those problems and significantly simplify the policy, but my solution would trample past edits of team members, and for all I knew it might break something. The team let me take a shot at it. The next day, we started our meeting, and to my surprise, they not only accepted my edits but liked them. This turned out to be a collaborative effort in which everyone enhanced the effectiveness of the others, focused on our objective, and we achieved success. In the end I did not feel like an attorney advising the drafting committee but simply felt like another member of the team.”

What our Attorneys Contribute Policy Officer editors have discovered the following about what their attorney colleagues contribute to crafting policy language:

- They do indeed wish to use clear, Plain English as much as possible; they are willing to work with the editors and compromise on language. The exception is where specific language has been established in case law and is imbued with specific legal meaning.

- They are aware of the subtle legal meaning that certain words or phrases have—this is training most editors do not have. They work with us to determine whether we can use simpler phrasing if we have to use the legal term or language.

- They have excellent editorial instincts and provide suggestions on the logical order of ideas and consistent use of terms, and which terms are appropriate.

- They can see how language and legal meaning have a very subtle interplay and how even seemingly small revisions can have an impact on the legal meaning and standing of policy text.

Ongoing Benefits of this Collaboration We have found it powerful and enlightening to see how beneficial this interaction between editors, attorneys, and policy owners can be. In the UVU Policy Office, we find ourselves amazed at how much we learn from our attorneys about the complex legal landscape of higher education. The Policy Office believes that this partnership results in well-crafted, effective policy. A metaphor for how this relationship works came from a recent team event: UVU OGC held its annual goal-setting retreat at a lovely cabin in the mountains of Utah. Afterwards, we went on a hike by taking a ski lift to the top of the local ski resort. We then hiked down to a beautiful, well-known waterfall. Although the hike was a descent, it was challenging for me. I had recently spent 6 weeks limping around with a cane due to a rogue knee. Having just started physical therapy and exercise to regain stability and function, I really wanted to go on this hike but had serious hesitations. The team encouraged me to go. Within a few minutes of stepping off the ski lift, a teammate stayed behind with me to make sure I made the descent safely. His companionship and care motivated me to not turn back, but to keep going. The group ahead stopped often to make sure we could catch up. Team members took turns asking me how I was doing, whether I needed water or a break, and if I needed assistance crossing the stream at the base of the waterfall. Then our manager and another coworker left the group early to retrieve his SUV and drive up the mountain as far as he could to shorten the distance from the waterfall back to the resort. Three coworkers walked me to the point where our manager picked us up, while the rest of the group took the regular trail down. Our team collaborated to make this hike enjoyable not only for me, but for all of us. Each person seemed to know instinctively what I, or any of us, needed in the moment. At one point, the team cheered on one of our teammates who has a fear of heights but took the lift up the mountain. Each teammate took turns taking care of each other. This is the core of any work we do in higher education—drawing upon the expertise of colleagues across many disciplines and collaborating to build not only solid policy, but institutions striving to fulfill their educational missions.

Tags:

accessibility

Cara O'Sullivan

collaboration

legal

partnership

Policy Development

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Christine Valentine, Concordia University of Edmonton,

Tuesday, July 15, 2025

Updated: Monday, July 14, 2025

|

A practical addition to your policy programAs a policy administrator, few accomplishments are more meaningful than helping a colleague navigate a complex policy project. One of the most fulfilling aspects of my role as Policy & Records Analyst is providing guidance and support, especially when policy development and review feel unfamiliar or overwhelming.

At Concordia University of Edmonton (CUE), a small university in Edmonton, Alberta, known for its strong sense of community, that supportive spirit extends to our policy work. Our approach emphasizes collaboration, clarity, and long-term sustainability, ensuring that institutional policies remain aligned with the university’s vision, mission, and strategic objectives.

When I joined CUE, my aim was to establish a consistent, university-wide process for developing and reviewing policies. Early on, I recognized that building an effective policy program involves more than setting rules or monitoring compliance. It requires meaningful engagement with the people who contribute to the work. At CUE, policy development is a shared responsibility. Developers come from across the institution, bringing diverse expertise and varying levels of experience in policy writing. To support their success, I created the Policy Developers’ Toolkit—a user-focused resource designed to empower policy developers to engage confidently and effectively in the policy development and review process. Why we created the toolkitCUE’s five-step policy development and review process is designed to be straightforward, consistent across all policy instrument types, and easy to follow:

- A new policy action (creating a new policy or revising or rescinding an existing one) is proposed through a Policy Document Action Plan.

- Upon endorsement, the policy owner assigns a policy developer or development team.

- The development phase includes benchmarking, drafting, and consultation.

- The policy is submitted to the Policy Review Committee for review.

- Final approval is sought from the appropriate institutional authority.

Although the process itself is simple on paper, Step 3—development and revision by the policy developer—is often the most challenging. Policy developers are typically subject-matter experts, but they may not be familiar with translating their expertise into policy language that is clear, concise , and helpful.

As I worked alongside developers, I realized that providing one-on-one support for each project would not be sustainable long-term. I began by sharing checklists and other key reference documents, but it soon became clear that we needed a more comprehensive, centralized resource. The goal was twofold: to build confidence and understanding among our developers and to enable me, as the policy administrator, to manage multiple projects efficiently while still offering meaningful support.

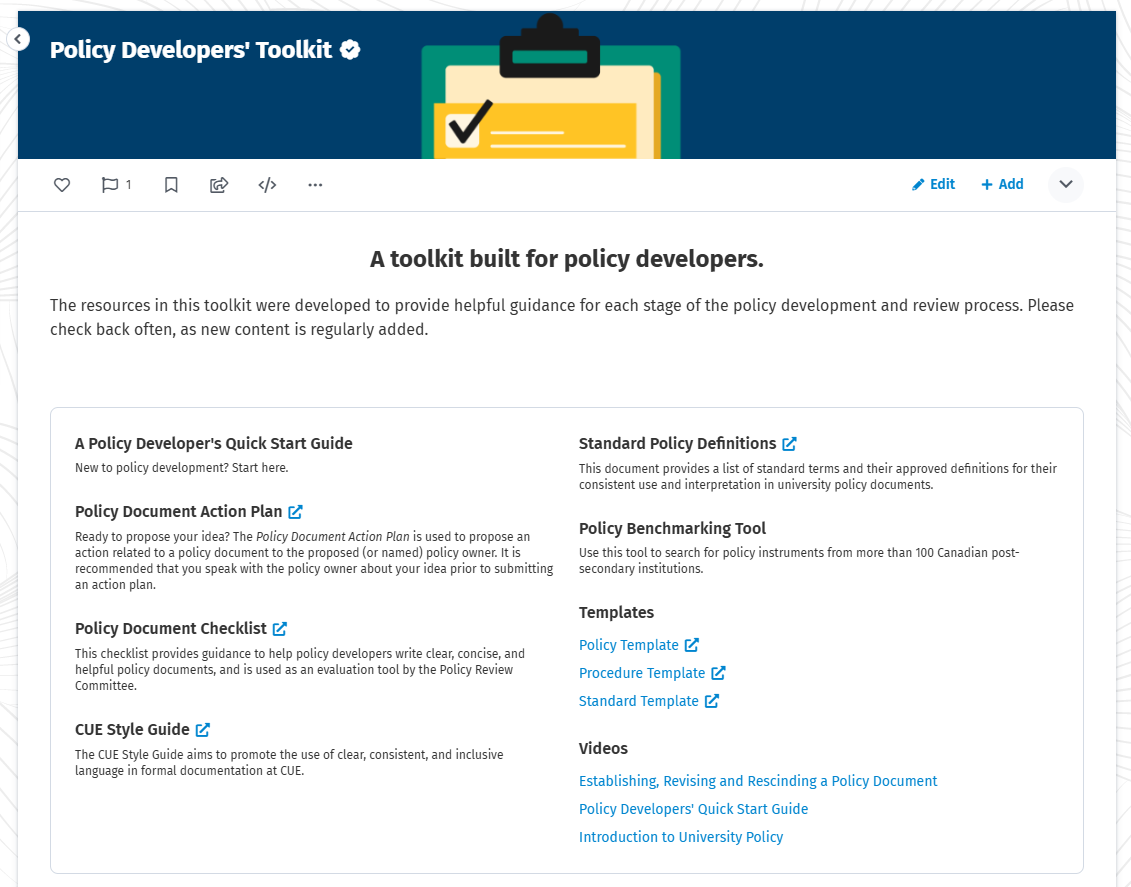

Bringing these resources together in a central repository also allowed me to understand how they worked together and identify any gaps. This insight allowed me to refine the tools, build coherence, and ensure the approach remained practical and user-friendly. What’s in the toolkit?The Policy Developers’ Toolkit is hosted in CUE Connect, our employee intranet. It is organized around the key stages of the policy development and review cycle, and is designed to meet developers where they are—whether they are new to policy work or more experienced.

Current resources include: - Policy Document Checklist – used by both policy developers and the Policy Review Committee to ensure policies are clear, concise, and helpful.

- Templates – standardized, fillable templates for various policy instruments.

- Standard Policy Definitions – to support clarity and consistency across all documents.

- Policy Benchmarking Tool – a custom Google search engine that scans 100+ Canadian post-secondary policy sites based on a keyword search.

- Instructional Videos – short walkthroughs, including a Quick Start Guide for new developers.

- Links to Key Resources – including our policy repository and essential documents like the Policy Document Action Plan.

Building Your Own ToolkitIf your institution does not yet have a policy development toolkit, or you are in the process of building one, here are a few steps I recommend:

- Find a Home for Your Toolkit: Use a central, easily accessible location such as an employee intranet.

- Start with What You Have: Gather existing resources like templates, checklists, and process guides.

- Communicate Often: Link to the toolkit in training materials, auto-replies, and communications with policy developers.

- Invite Feedback: Engage your users to learn what is working and what could be improved.

- Review and Improve: A good toolkit should evolve with your policy program. Make updates a regular part of your work.

When we launched our toolkit, it coincided with significant revisions to our Policy on University Policy Documents. This timing allowed the toolkit to support implementation and promote a smoother transition. A well-timed, accessible toolkit can be a powerful aid in navigating institutional change. Final Thoughts: Policy as a Community EffortTo me, policy work is one of the ways we express care for our institution and for one another. The Policy Developers’ Toolkit reflects that care by prioritizing clear guidance and accessible support to help our colleagues navigate what can sometimes feel like a complex process. While it is a practical tool, I also see it as a statement: policy work matters, and the people doing it deserve the right support to do it well.

Over time, consistent communication helped embed the toolkit into CUE’s institutional culture. It has become a staple in our policy trainings, a standard reference in policy-related email communications, and a key component of our broader efforts to promote policy literacy. Housed within our centralized hub for policy information, the toolkit makes it easy for employees to find the right resources at the right time.

As the toolkit becomes further integrated into our policy infrastructure, we continue to expand its scope. Planned additions include interactive training modules and workshops designed to build engagement and deepen institutional capacity in policy development. In this way, the toolkit is not a static product, but a growing and evolving support system that reflects our commitment to a thoughtful, community-centered approach.

As policy administrators, we know that policy work is both foundational and deeply human. While our documents provide structure, it is the people who shape them. The support they receive plays a vital role in ensuring policies reflect our institutional values and serve our communities well. By investing in the individuals who create and revise our policies, we help foster a culture of collaboration, inclusion, and shared purpose.

-

If you have tools or strategies that have proven helpful in your own policy toolkit, or if you are currently building one for your institution, I warmly invite you to share your insights and experiences. Please feel free to leave a comment or reach out to me at christine.valentine@concordia.ab.ca. I look forward to connecting and learning from your journey.

Attached Thumbnails:

Tags:

Christine Valentine

policy development

policy writer

resources

toolkit

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

|

Posted By Monique Everroad, Clemson University,

Tuesday, June 17, 2025

Updated: Friday, June 13, 2025

|

The group project no one asked forIt was the evening of December 23, 2024. Many policy administrators already turned on their automatic-replies and were preparing for a few days (or a couple weeks) of well-deserved vacation, away from all of those relentless emails and news alerts. It was then, when no one was looking, that H.R.5646 was signed into law. A new email from the Clery Center pinged in inboxes but there was no one there to hear it. If you were one of the lucky policy administrators, someone at your institution gave you a heads up about the bill—now, the Stop Campus Hazing Act (SCHA)--while it was making its way through congressional approvals. Perhaps your institution already assembled a team and was ready to create or revise a new hazing policy. But alas, most policy administrators returned to skeleton offices after a few days off or worse, did not return until mid-January, and waiting in our inboxes was a loud ticking clock – a new regulatory deadline that was less than six months away. The Dreaded Group ProjectPanicMy new year’s resolution had included not taking responsibility for other people’s job duties and SCHA was teeing me up for a failed resolution. Like many policy administrators, I needed to know who was leading the charge on this project. To nod to Alison Whiting’s Policy Matters post last month, policy administrators are often pulled into drafting teams with varying degrees of direction, engagement, and success. SCHA is complex and meeting the deadline would require more cross-campus collaboration and speed than most policy projects. So, when I returned to the office after two weeks of blissful vacation, I (choosing optimism) looked for a special meeting invite, a notification from being added to a new collaboration folder, or even just an email thread (anything!)... Nothing. HopeAlas! I didn’t have to panic for long. The invite, folder notification, and emails started mid-January, and we were off to the races. I can look back at the past few months, now, with the deadline for SCHA just a few days away, and confidently say my new year’s resolution remains intact. From a policy administrator’s perspective, the SCHA project execution was a success at my institution, especially when it came to policy development and revision. Here’s why I think it succeeded. Team > GroupThe PeopleFrom the beginning, leadership set the tone. The project was led from the top by two executive leaders. Their commitment and engagement kept the project moving and gave it the gravity it needed to stay on track. Leadership also ensured that all known stakeholder groups were represented on the project team. Even better, the representatives pulled in were decisionmakers and implementers. This had significant impact when it came to keeping discussions productive and outcomes actionable. The PlanA plan was clearly defined from before the very first meeting. Regular project all-team meetings were added to our calendars. At the first meeting, deliverables and assignments were outlined upfront, and the policy approval workflow was used to work backwards to help set deadlines. The project team divided into subcommittees with one focused solely on drafting our Hazing policy’s revision. Having these smaller groups made it easier to make swift decisions and produce materials with clear requests or challenges to discuss when the larger team reconvened. All committee materials were shared and organized in a single collaboration folder. Clear direction and required transparency allowed each team member to go “All in.” (IYKYK) The DiscussionsThe entire project team worked efficiently. Within the policy subcommittee, emails received quick responses, assignments and drafts were reviewed prior to our meetings. Each of us knew our particular role in the subcommittee and we leveraged the others’ strengths and expertise to come to a consensus on language. For example, our previous definition of hazing required modifications to meet the new requirements in the SCHA definition. We realized we were drafting an endless list of examples and pinning our conduct office in a corner. What if we said “paddling” but left out “spanking” or “whipping?” Wasn’t it all physical harm? If we categorized our examples, we could make sure the definition endured the constant evolution of hazing practices we see with each new incoming class. We adopted this approach for the rest of the policy. If we stayed broad, it allowed the student conduct and human resources offices to lean into their established procedures to handle each report on a case-by-case basis. Because these conversations and details were hashed out in smaller meetings, we confidently presented our recommendations to the larger team. With some questions, but very few requests for changes, the policy moved forward. Our small group trusted each other and the project team trusted us. The FoundationAny project team can fall into the trap of trying to reinvent the wheel. Sometimes it’s necessary. But with less than six months to pull together a policy, trainings, and update processes, taking advantage of what was already in place helped the project team move quickly. The other subcommittees looked at their processes and resources and saw where they could make tweaks just like the policy subcommittee did. As the group came together, we were able to lean into the expectations of the policy. We asked: Does the policy support the procedures? Does it clearly state the requirements needed to hold people accountable? Can the policy be enforced? Does it provide enough latitude for the breadth of the subject matter? As policy administrators, we ask these questions of our policy owners and writers often. It can seem second nature for us, but when asked aloud to a large project team and confirmation was received, the significance of our policy writing standards stood out. I must also point out a couple foundational components we were able to leverage that I know some policy administrators could not. - Clemson already had a Hazing policy.

- South Carolina law requires higher education institutions to track and report certain hazing violations.

These allowed project team members to show up prepared for the group discussions and to update their practices, expand services, build webpages, and revise a policy. And then we had our champions in leadership who set their expectations for us all and kept the momentum all the way to the end. While I would never wish on any policy administrator another “middle-of-the-night-while- everyone’s-asleep legal requirement to comply with in six months" it was an inspiring experience to see colleagues across campus shine in their areas of expertise, collaborate quickly and effectively, and build trust as a group—ultimately becoming a team. This project gives me hope for future ones and ideas to help course correct others. I want to give a HUGE shout out to everyone on the project team from Clemson University’s division of student affairs, office of access compliance and education, marketing and communications, office of general counsel, division of public safety, and office of university compliance and ethics! Well done, team. Go Tigers! *Please note: at the time of the original publication of this post, Clemson's revised Hazing policy is pending president approval and is not yet publicly available. Visit Clemson University's Policies site on June 23rd to read the final version.

Tags:

collaboration

deadline

group project

hazing

Monique Everroad

regulation

teams

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Alison Whiting, Mount Royal University,

Tuesday, May 20, 2025

Updated: Monday, May 19, 2025

|

The benefits and challenges of drafting by committee

I think it is no small secret that universities love a committee. Whether you call them committees, working groups, task forces, advisory groups, steering committees, or something else entirely, it would not surprise me to learn that your university has

these in abundance. If there’s a problem, there’s probably a committee being formed to find the solution.

But I jest. Committees (advisory groups, task forces, etc.) are an integral component of collegial governance. And in many ways,

there are indisputable benefits to having a cross-institutional committee weigh in on policy decisions that have broad campus impacts.

Benefits such as:

- Breadth of expertise: Universities are awash with subject matter experts and their expertise can help ground the policy in the context of the university’s campus culture and history.

- Cross-divisional representation: Including representation across different divisions of the university helps create well-rounded and inclusive policies and ensures relevant application in all areas.

- Proactive stakeholder consultation: Early input from relevant stakeholders can speed up the policy approval process by identifying and addressing issues right away.

- Improved uptake: When more people have been involved in the policy process it creates a sense of shared ownership which can lead to better buy-in and uptake during the operationalization of the policy.

However, the question at the heart of this blog post is: Is drafting by committee the most effective strategy for policy writing? And I’m not so sure that it is. While we want to ensure we are capitalizing on the wealth of expertise available

on campus and gathering the relevant people in the room, we also run the risk of the proverbial “too many cooks in the kitchen.” And when we have too many cooks in the kitchen, we can end up with a policy that includes everything and the kitchen sink.

Drafting by committee can lose sight of the overall objective.

The challenge with drafting by committee is that we can quickly lose sight of the overall objective as everyone starts getting into the weeds about what the policy needs to say and how it needs to be said. People come to the table with their own personal

objectives of what they believe the policy needs to cover, and if they successfully convince the rest of the committee to include each of those objectives or pieces of information, we can quickly end up with a policy draft that is unwieldy.

Drafting by committee can cause logistical challenges.

Challenges such as coordinating meetings, keeping people on task, waiting for each committee member to weigh in on decisions, coming to consensus with there are differing opinions and perspectives, time spent wordsmithing the language so that we can land

on a message that's not only precisely accurate, but accurately precise while also artfully exact, with every word pulling its semantic weight. Or at least that’s what the linguists in the room tell me.

So how and when can we use committees in our policy process?

My personal preference is to capitalize on existing committees as part of an early consultation process. As we covered at the start of this blog, it is highly likely that you already have a plethora of committees at your disposal. There is likely one,

if not two or three or four, committees scattered across campus that include relevant subject matter expertise and cross-institutional representation that you could utilize to help inform the policy without actually asking them to write it.

Why ask people to form and join yet another committee when you can simply go to them? Instead, consider:

- Take the existing policy (or the plan for a new policy) to the committee and ask the committee members to identify their top one to two pain points with the policy.

- Take that information away, and use it to help inform the new draft.

- Bring the new draft back to the committee for feedback.

The key to this process is to let the committee know they are not “the owners” of the policy, you are there seeking their feedback and expertise, but that ultimately the policy drafter is making the final decision on the scope, content and language of

the policy.

This process can be repeated with however many relevant committees or groups exist on campus relative to the topic of the policy being drafted or revised. Utilizing existing committees in this way helps reap the benefits, while sidestepping the challenges.

Whether you always write policy by committee, never write policy by committee or occasionally find yourself writing policy by committee, this blog post has hopefully sparked some reflection on the value and pitfalls of drafting by committee.

Tags:

collaboration

committees

drafting policy

how-to

policy development

policy process

writing

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Monique Everroad, Clemson University,

Tuesday, April 22, 2025

Updated: Tuesday, April 22, 2025

|

An exercise in finding hope in times of uncertainty + practical takeaways for policy administrators This is not your typical policy post. I contemplated blog topics for months and everything that I came up with seemed pointless in the current chaos of our world as policy administrators. I was losing hope – fast. So, I wrote a "Dear Abby Letter" and let ChatGPT play the role of Abby. The results surprised me and prompted this post. (Abby's response was modified for length and audience.)

This was an exercise for me to find hope in my work again. It helped me identify practical ways to weather the storm and I hope it does the same for you.

Dear Abby: I am a public servant working in higher education and, recently, it feels like my world is a shaken snow globe, flipped upside down. I am passionate about this industry and believe a university is THE COOLEST place to work. I know that those who work in higher education help make dreams come true and change lives for the better.

But in the past few months (well, maybe years) my work has been turned against me. You see, my role is to help ensure our university has policies that comply with federal and state rules, and to help members of my university know and understand these rules. Lately, the rules are changing at lightning speed, outside of normal processes, and are unlike anything I've had to help manage before. I'm no stranger to putting my head down and getting the work done or to swallowing my dissenting opinion on how things are executed. But right now, I feel like my values are being challenged. I KNOW my personal values are being violated, but my professional values, the ethics that are the foundation of my work, are being distorted.

Higher education is also facing huge financial challenges and I'm not certain about my professional future. Will I have to find a new job? Will I have to fall in love with a new industry? Usually, I turn to the university I serve and find hope in the students from all over the world, the mind-blowing research, and the energy that comes from innovation and growth. I'm losing hope. How do I weather this storm when it's a complete whiteout? - Shaken Snow Globe

Dear Shaken Snow Globe: First, let me say this: you are clearly someone who cares deeply—not just about rules and regulations, but about people, purpose, and doing what’s right. That kind of commitment is admirable.

It’s no small thing to feel your professional values—those carefully built foundations—being shaken. When the work you once saw as noble begins to feel compromised, it’s not just disorienting, it’s heartbreaking. And in higher education, where the stakes are high and the resources low, that heartbreak can be compounded by exhaustion, uncertainty, and loss of purpose.

Rest assured, that even though the system is strained and the mission muddled, your values and talents are intact—they are your compass.

When your world feels like a total whiteout, the key is not to force clarity all at once, but to anchor yourself to what you do know: - You know what you stand for.

- You know what doing the right thing looks like.

- You know your impact matters—even when it feels invisible.

In this storm, focus on finding even the smallest moments of alignment: a student who “gets it,” a colleague who shares your values, a task that feels true to your mission.

And as for your future—remember, uncertainty is not the enemy. It may be the invitation.

You asked, how do I weather this storm? The same way you’ve done your entire career: with courage, clarity, and conviction. But don’t try to do it alone. Talk to mentors. Seek allies. And if hope feels low—borrow some from those who believe in you.

The snow will settle. And when it does, you’ll still be standing—values intact, clearheaded, and compass pointing forward.

With empathy and encouragement,

Abby

Weathering the Policy Storm: Practical Tips for Policy Administrators The landscape of higher education is shifting rapidly, but there are steady practices and strategies that can help institutions not only survive but lead with clarity and integrity through turbulent times. Policy administrators are some of the most equipped people to navigate these storms.

Below are practical ways policy administrators can stay grounded and regain hope.

Lean into what’s already established and focus on what you can control.- You’re prepared for this. Think about the standards, templates, systems, and processes you’ve developed or improved over the years. That’s your foundation.

- Leverage the Policy on Policies. When institutional policies must change quickly, ensure those updates still follow an approved process. If an expedited path doesn’t yet exist, document how decisions are made. Don't be afraid to lean on what you're known for -- consistency. Remind your leadership that how they choose to navigate a challenge today sets precedent for how the institution navigates similar challenges in the future.

- Don't skip documentation. It’s tempting to cut corners when under pressure, but accurate documentation—who was involved, what changed, when, and why—is critical for transparency and accountability.

- This is your bragging right: You know how to write effective policies that create guardrails for legal and ethical decision-making. Broad, well-written policies allow flexibility while ensuring requirements are met. Don’t underestimate how critical that is—especially now.

Celebrate the wins—big and small.

- Some of the changes in this storm are good changes. Think of the Stop Campus Hazing Act. It’s absolute chaos as we sprint towards the deadline, but we're helping create safer, more accountable environments.

- Crisis = Collaboration. Remember how quickly departments rallied during COVID? Urgent challenges often lead to increased cross-campus collaboration, more focused meetings, and stronger shared accountability.

- Tough moments reveal true partners. This moment is also clarifying. Like an outdated policy, it's what was believed to be true, but wasn't, that often causes the damage. In this storm you’ll discover who runs toward collaboration and who puts up walls. You’ll likely find new allies—and maybe feel let down by some familiar faces. Either way, clarity is a gift.

Reevaluate professional skills. You are talented.

- You do more than policy. Whether it’s sending concise yet informative emails, updating web content, coordinating teams, or managing complex changes—you are a multidimensional force with a wide range of skills. Just in case you have a hard time pinpointing these skills, I listed them here for you: adaptability, administrative coordination, attention to detail, change management, collaboration, compliance knowledge, continuous improvement, copyediting, critical thinking, data analysis, data tables/Excel, document management, ethics and discretion, leadership, presentation design, program management, project management, research, risk assessment, strategic planning, technical solution implementation and management, technical writing, time management, written and oral communication, and many more.

- Know your worth. You are valuable regardless of any threats to your values and beliefs that you have to face when you go to work. Continue to be you and find comfort knowing that you are not what is drastically changing.

- Knowing your worth can also mean reassessing your role or institution. It’s an unsettling thought, but it can also reveal new opportunities and affirm personal and professional priorities. With your skills and character, don't let this storm bury you because you're afraid to let go.

Final Reflection: Gratitude for Purposeful Work This work is hard—but I love it enough that it shakes me to my core when it feels threatened. That’s a gift, because not everyone gets to feel so deeply about what they do.

This storm is a reminder of the value and resilience embedded in the work we do—and the important role we play in guiding our institutions through change.

Tags:

Dear Abby

difficult times

hope

Monique Everroad

values

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Cara O'Sullivan, Utah Valley University,

Tuesday, March 18, 2025

Updated: Friday, March 14, 2025

|

In recent years, state legislatures have increased their scrutiny of higher education, resulting in substantial legislation that impacts institutional policy. Depending on the length of the legislative session in your state and the deadlines legislators set for laws and required policies to go into effect, this can inflict quite a time crunch on staff in the Office of General Counsel and policy offices. (In Utah, the legislative session lasts 45 days, from January through early March.) In this article, I will discuss the process we set up at Utah Valley University (UVU) to track legislation that would affect policy, to organize policy revisions, and to assign appropriate changes to policy owners and attorneys who have the applicable subject matter expertise. I will also discuss a policy process we implemented four years ago called the compliance policy process, which is reserved for policy actions required by changes to state and federal law. Policy Development Process In Utah, the Utah System of Higher Education’s (USHE) General Counsel conducts a monthly meeting with policy office managers across our system and a separate meeting with attorneys across the USHE system. In these meetings, USHE General Counsel shares any upcoming changes to federal regulations and state code that could impact USHE and institutional policy. During the legislative season, USHE maintains a list of bills going through the state legislature and flags whether they are significant to higher ed or related to campus law enforcement and notes who the stakeholders throughout the system are. Throughout the legislative season, our General Counsel works proactively with their counterparts across the USHE system to help institution leadership provide input into bills that will impact our institutions. In turn, our General Counsel keeps the Policy Office updated on bills making their way through the legislative process. UVU’s General Counsel and the Policy Office then determine which bills apply to areas of our institution and which may require us to create new policies or revise existing ones. We then map the legislation to the applicable university policy and the attorney with appropriate subject matter expertise. We contact the policy owners to alert them to the upcoming policy action because they will need to approve any revisions and note the date by which policies must go into effect. Our policy office has two full time editors and an editorial intern, who split responsibility for editing the necessary policy changes. Through our project tracking system, we document the progress of policy drafts in the review process and ensure Policy Office editors, policy owners, and assigned attorneys have all reviewed and approved the policy drafts. We then submit the drafts through our compliance policy process to President’s Council and the Board of Trustees. Compliance Change Before we developed the compliance change policy process, we relied on our temporary emergency process to implement policies by the dates set by new laws. Per our Policy 101 Policy Governing Policies, we were obligated to submit the temporary emergency policy through the regular policy process and obtain university community commentary. Four years ago, when revising Policy 101, we determined that we needed a policy process to accommodate policy actions mandated by changes to state and federal law that often have tight compliance deadlines. We also reasoned that these mandated policy actions were not subject to the full notice and comment stages because we are required to comply with federal and state legislation. In the compliance change process, the policy draft goes to President’s Council for approval and goes into effect upon that approval. The Board of Trustees may later ratify or disapprove the policy. Even though the university community does not have a formal commentary period in this particular process, the UVU Policy Office is still tasked with making policy decisions transparent. So, with each compliance change, we work with the Office of General Counsel and the policy owners to craft an executive summary that explains the legal requirements for a compliance change. We provide this document on our news blog. This assures the university community that university leadership has adhered to our shared governance model and formal policy process. When first implemented, our compliance change process applied only to limited scope revisions to passages of existing policy or deletions of a policy. But as legislation mandating deep changes to higher education began sweeping across the country, we realized we had to expand the compliance change process to the creation of new policies. Getting Ahead of the Game Proactively monitoring legislation and planning for policy changes mandated by legislation helps us avoid a huge rush that can occur at the end of a legislative session—especially when deadlines to place policies into effect can be very tight. This process helps us identify appropriate policy owners and attorneys and adjust workloads as best as possible. In the current environment in which higher education leaders and policy managers find themselves, staying organized and planning proactively can help us better deal with the changes sweeping across our industry.

Tags:

Cara O'Sullivan

federal government

legislation

mandates

policy changes

policy process

proactive

state government

Permalink

|

|

|

Posted By Olivia Welsh, student, UNC - Chapel Hill,

Tuesday, February 18, 2025

Updated: Wednesday, March 19, 2025

|

The Underrated Role of Understanding LanguageRules for policy writing, like the training and resources offered by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s (UNC-Chapel Hill) Policy Office, are helpful tools to improve the overall accessibility and utility of policies. However, as is true in almost all fields, rules have their limits. It never makes sense to apply the same rules to every piece of policy writing. Policy writers need to consider how language furthers their policy goals and institutional values. In order to understand when the “rules” are useful and when they should be ignored, policy writers and editors need to be familiar with why guidelines are given. Fortunately, this is exactly the type of question linguists study: how does human cognition interact with language, and how can that information be used? From this perspective, policy administrators can better examine and justify writing and editing decisions. This is illustrated by looking at a few examples of common policy-editing rules.

Rule: Remove Barrier LanguageOne of the most obvious changes in updated policy language is the removal of marginalizing or otherwise exclusionary words. This includes gendered terminology, non-preferred labels, or unnecessarily limited categories (e.g., outdated country names, normative descriptors). Generally, though not always, this rule of using inclusive language is conceptually understood – why be exclusive when you could be inclusive? Still, it can seem trivial for organizations to devote resources to combing through old policies, looking for violations of inclusivity rules and making tiny changes. The field of sociolinguistics provides a lot of evidence that this investment is actually not trivial at all. For example, the use of gendered terminology triggers mental concepts of gender categories, making gendered stereotypes more accessible in the mind. This unconscious process has very real consequences on behavior. When masculine forms are used as “neutral” (e.g., “mankind”), it promotes stereotypes that male is the default, expected category – making those who do not identify as male feel less suited to the environment. A 2021 study of adults in Israel demonstrated that addressing women with masculine (neutral usage for Hebrew) pronouns in online math testing resulted in poorer performance, whereas feminine testing language reduced the gender achievement gap by one-third. The converse held for men, who performed worse when addressed in the feminine. Furthermore, both genders exhibited more effort (measured in time) when taking a test with language corresponding to their gender identity (Kricheli-Katz & Regev, 2021). The use of gendered language influenced the perception of the “prototypical test-taker,” making those of a gender not addressed directly in the test’s language feel alienated from the field of mathematics. The simple act of changing pronouns to be properly inclusive significantly improved test-takers’ attitudes and achievement. In Sweden, a gender-neutral pronoun was officially incorporated into their language in 2015. This faced backlash, being criticized as a performative action of “political correctness” with little tangible impact (Tavits & Pérez, 2019). Yet experiments here again reveal that gender-neutral pronoun use weakens people’s bias favoring men, and that this reduced salience of masculinity promotes more equal attitudes towards women and members of the LGBTQ+ community. This was displayed in more positive attitudes toward female politicians and less hostility towards LGBTQ+ individuals, and more support for policies that benefit both groups (Tavitz & Pérez, 2019). These results should be hugely important in the world of higher education policy and administration. The purported goal of education is to promote opportunity without discrimination. By this standard, it is problematic to use language in policies that makes certain groups or individuals feel alienated because this negatively impacts their academic performance and undermines their sense of belonging in the institutional setting. As such, removing barrier language is not about “following the rules” just because they exist, but about recognizing the very real impacts that language has on behavior and ensuring that the attitudes of an institution are represented correctly in policy. As language continuously evolves and preferred, maximally inclusive language changes, a review that is sensitive to the realities of how policy language impacts people is an essential tool. Rule: Avoid Negative StatementsLooking at more technical elements of policy review guidelines, let’s consider the long-promoted practice of avoiding negative statements. Or, to state the rule more simply: no negative statements. Interestingly, this rule is clearer when stated in a way that violates the rule itself. So why is it such a common recommendation for clear writing?

Traditionally, proponents of avoiding negative statements in policy cite processing difficulties and assert that telling people what to do is more helpful than telling them what not to do. It’s not that these ideas are “wrong.” However, linguistic evidence reveals a more complicated picture than any rule could account for.

In some regards, the “no negative statements” rule has obvious applicability. If a policy intends to have employees submit paperwork to the Human Resources department, saying “submit paperwork to the Human Resources department” is more informative and useful than saying “do not submit paperwork to the Finance department.” A rule to avoid negative statements helps ensure actionable policy statements. Some statements, however, have equally informative positive and negative versions (when they refer to a binary). Still, negative statements have been found to be more cognitively demanding than positive statements (Agmon et al., 2022). This phenomenon is demonstrated in simple experiments measuring reaction time in verification tasks of statements like “the square is blue” and negated statements like “the square is not blue.” The delay of task completion for negative sentences can sometimes be attributed to processing cost (for example, some linguistic theorists posit that double-processing is necessary for negation: first processing a situation to then be able to process its negation). Negation also has a verification cost, which is an additional effort to determine the truth value of a negative sentence (Agmon et al., 2022). Another concern is that negation often increases structural complexity by requiring the addition of auxiliary verbs (e.g., in a sentence like “The student reads,” negation requires the addition of the auxiliary verb “do,” in the form “The student does not read”). Difficulties can also arise from a pragmatic perspective, since readers find negation to be strange if the specific context does not invoke it. In other words, if there is no expectation of some positive statement, it is hard for readers to determine the relevance of its negation (Nordmeyer & Frank, 2014). As such, policies that include negative statements carry a contextual burden that may be lessened by avoiding negative statements.